Phenotype Plasticity The same genotype can result in different phenotypes because environmental conditions affect patterns of gene expression in an organism. For example, a single fox exhibits different phenotypes in summer and in winter. So, this statement describes an example of phenotypic plasticity.

Continuous Variation Unlike Mendel’s pea plants, humans don’t come in two clear-cut “tall” and “short” varieties. Instead, humans come in many different heights, and height can vary in increments of inches or fractions of inches.

Complex Inheritance Pattern Tall parents can have a short child, short parents can have a tall child, and two parents of different heights may or may not have a child a in the middle. Siblings with the same two parents may have a range of heights, ones that don’t fall into distinct categories.

How is height inherited? Height and other similar features are controlled not just by one gene, but by multiple genes that each make a small contribution to the overall outcome. This inheritance pattern is sometimes called polygenic inheritance. For instance, a recent study found over 400 genes linked to variation in height.

When there are large numbers of genes involved, it becomes hard to distinguish the effect of each individual gene, and even harder to see that alleles are inherited according to Mendelian rules. In an additional complication, height doesn’t just depend on genetics: it also depends on environmental factors, such as a child’s overall health and the type of nutrition he or she gets while growing up.

Polygenic Inheritance Human features like height, eye color, and hair color come in lots of slightly different forms because they are controlled by many genes, each of which contribute some amount to the overall phenotype. For example, there are two major eye color genes, but at least 14 other genes that play roles in determining a person’s exact eye color.

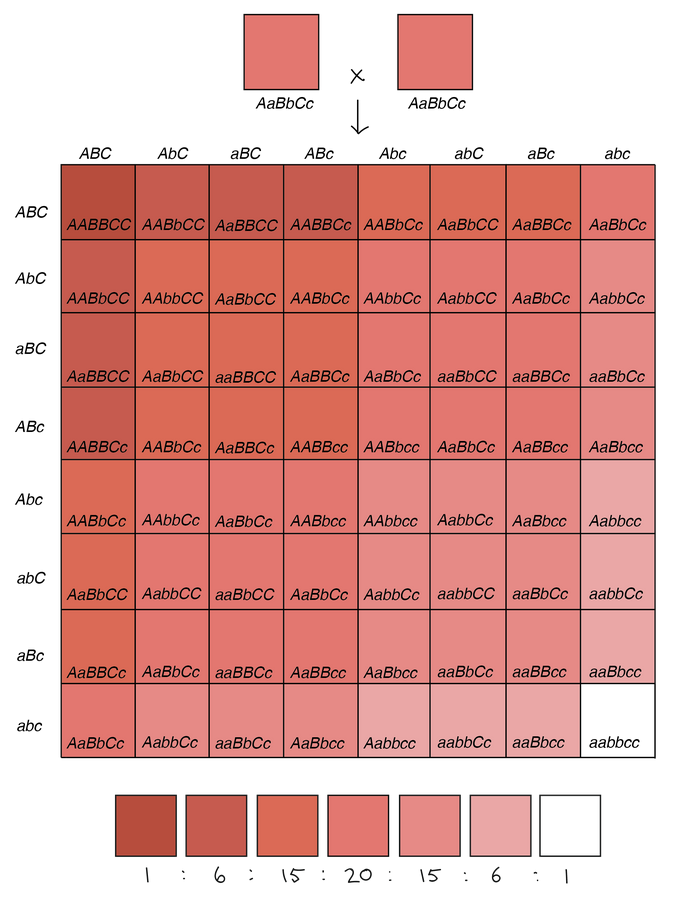

We can use an example involving wheat kernels to see how several genes whose alleles “add up” to influence the same trait can produce a spectrum of phenotypes.

In this example, there are three genes that each make reddish pigment in wheat kernels, which we’ll call A, B, and C. Each comes in two alleles, one of which makes pigment (uppercase) and one of which does not (lowercase). These alleles have additive effects: the aa genotype would contribute no pigment, the Aa genotype would contribute some amount of pigment, and the AA genotype which would contribute more pigment ( twice as much as Aa). The same would hold true for the B and C genes.

Imagine that two plants heterozygous for all three genes (AaBbCc) were crossed to one another. Each of the parent plants would have three alleles that made pigment, leading to pinkish kernels. Their offspring, however, would fall into seven color groups, ranging from no pigment whatsoever (aabbcc) and white kernels to lots of pigment (AABBCC) and dark red kernels. This is in fact what researchers have seen when crossing certain varieties of wheat.

This example shows how we can get a spectrum of slightly different phenotypes (something close to continuous variation) with just three genes. Increasing the number of genes would get even finer variations in color, or in another trait such as height.

Environment Effects Phenotypes also vary because they are affected by the environment. For instance, a person may have a genetic tendency to be underweight or obese, but his or her actual weight will depend on diet and exercise (with these factors often playing a greater role than genes).

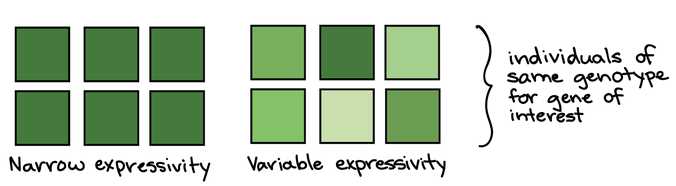

Variable Expressivity and Incomplete Penetrance Even for characteristics that are controlled by a single gene, it’s possible for individuals with the same genotype to have different phenotypes. For example, in the case of a genetic disorder, people with the same disease genotype may have a stronger or weaker forms of the disorder, and some may never develop the disorder at all.

In variable expressivity, a phenotype may be stronger or weaker in different people with the same genotype. For instance, in a group of people with a disease-causing genotype, some might develop a severe form of the disorder, while others might have a milder form.

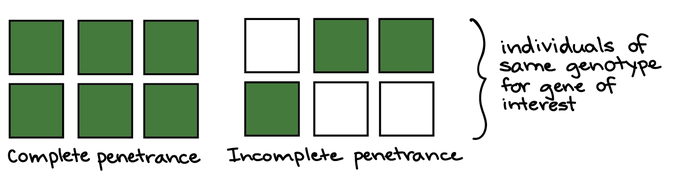

In incomplete penetrance, individuals with a certain genotype may or may not develop a phenotype associated with the genotype. For example, among people with the same disease- causing genotype for a hereditary disorder, some might never actually develop the disorder. The idea of penetrance is illustrated in the diagram below, with green or white color representing the presence or absence of a phenotype.