Eukaryotic Gene Transcription Genes are stored deep inside a cell, in a locked room called the nucleus. Ribosomes, the machines that assemble proteins, live outside the nucleus, floating around in a soup of chemicals called the cytosol. This spatial separation presents a logistical hurdle for the cell. A ribosome needs the instructions in a gene to put the corresponding protein together, but the genes are trapped inside the nucleus. How do the instructions in a gene get out of the nucleus and to the ribosome?

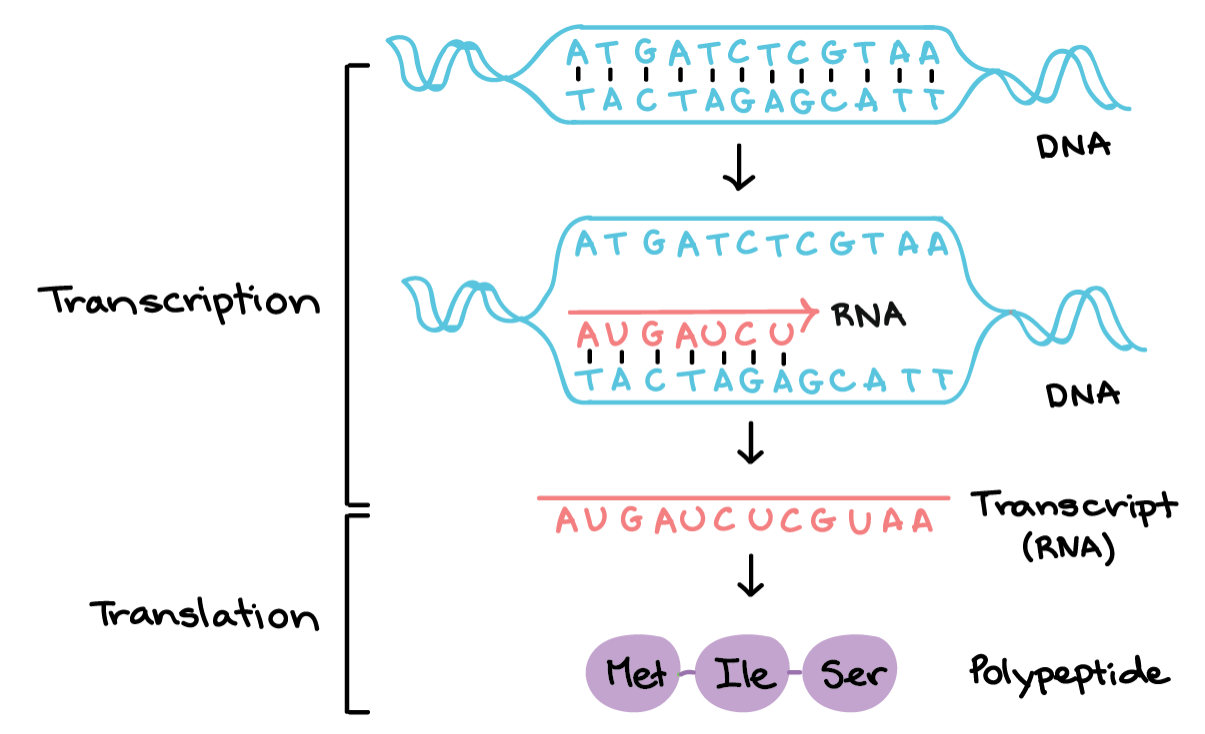

The instructions in a gene (written in the language of DNA nucleotides) are transcribed into a portable gene, called an mRNA transcript. These mRNA transcripts escape the nucleus and travel to the ribosomes, where they deliver their protein assembly instructions. The creation of mRNA transcripts (the creation of these portable genes) is called gene transcription.

Differences between DNA and RNA DNA

- Phosphodiester

- Deoxyribose

- Adenine, thymine, guanine, cytosine

- Information storage

RNA

- Phosphodiester

- Ribose

- Adenine, uracil, guanine, cytosine

How is an mRNA transcript made? An mRNA transcript is made by an enzyme called RNA polymerase II. The function of RNA polymerase II is broadly similar to DNA polymerase. The only high-level difference is in the building blocks used.

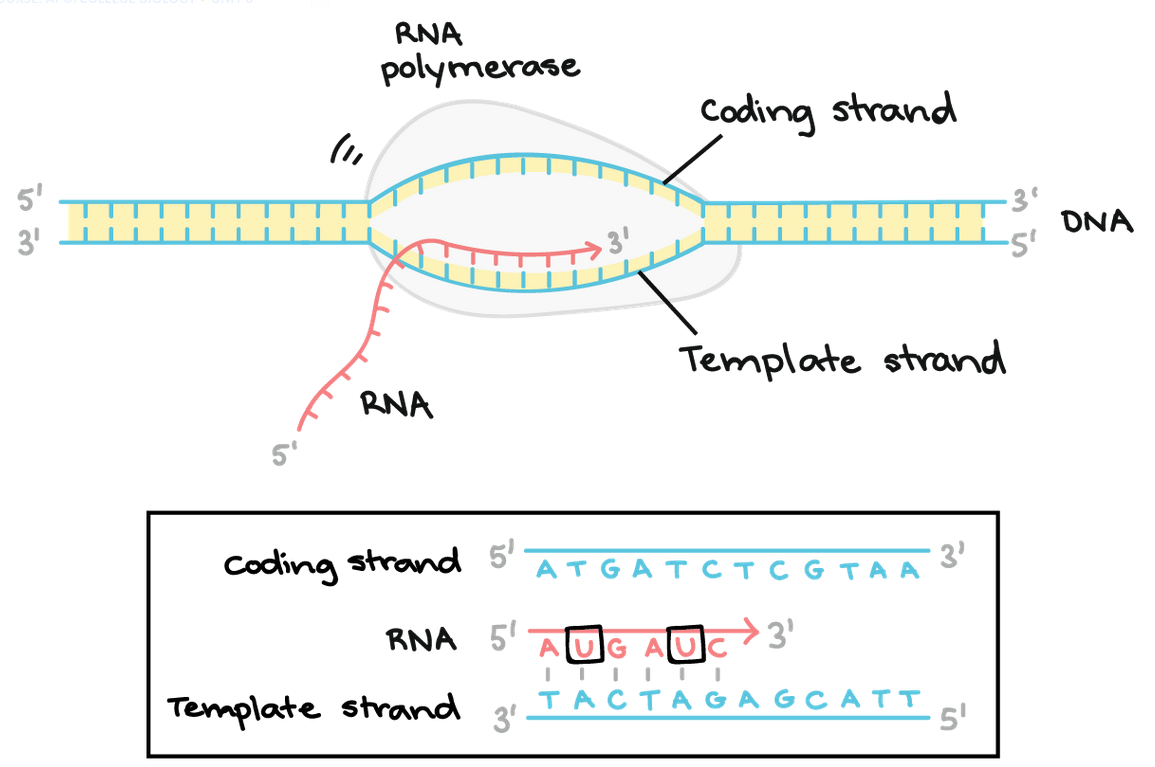

DNA polymerase uses a single strand of DNA as a template and synthesizes a strand of DNA. Each nucleotide in the synthesized DNA strand is complementary to the nucleotide in the template strand. RNA polymerase II also uses a strand of DNA as a template. Instead of using this template to make a complementary strand of DNA, it uses it to make a complementary strand of RNA — the mRNA transcript.

Key Points

- Transcription is the first step in gene expression. It involves copying a gene’s DNA sequence to make an RNA molecule.

- Transcription is performed by enzymes called RNA polymerases, which link nucleotides to form an RNA strand (using a DNA strand as a template).

- Transcription has three stages: initiation, elongation, and termination

- In eukaryotes, RNA molecules must be processed after transcription: they are spliced and have a 5’ cap and poly-A tail put on their ends.

- Transcription is controlled separately for each gene in your genome.

Overview of Transcription Transcription is the first step in gene expression, in which information from a gene is used to construct a functional product such as a protein. The goal of transcription is to make a RNA copy of a gene’s DNA sequence. For a protein-coding gene, the RNA copy, or transcript, carries the information needed to build a polypeptide (protein or protein subunit). Eukaryotic transcripts need to go through some processing steps before translation into proteins.

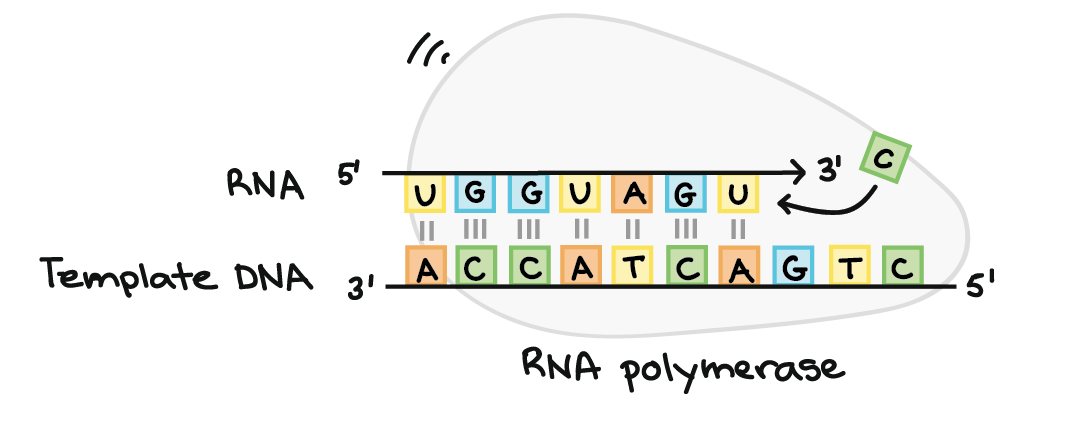

RNA Polymerase The main enzyme involved in transcription is RNA polymerase, which uses a single-stranded DNA template to synthesize a complementary strand of RNA. Specifically, RNA polymerase builds an RNA strand in the 5’ to 3’ direction, adding a new nucleotide to the 3’ end of the strand.

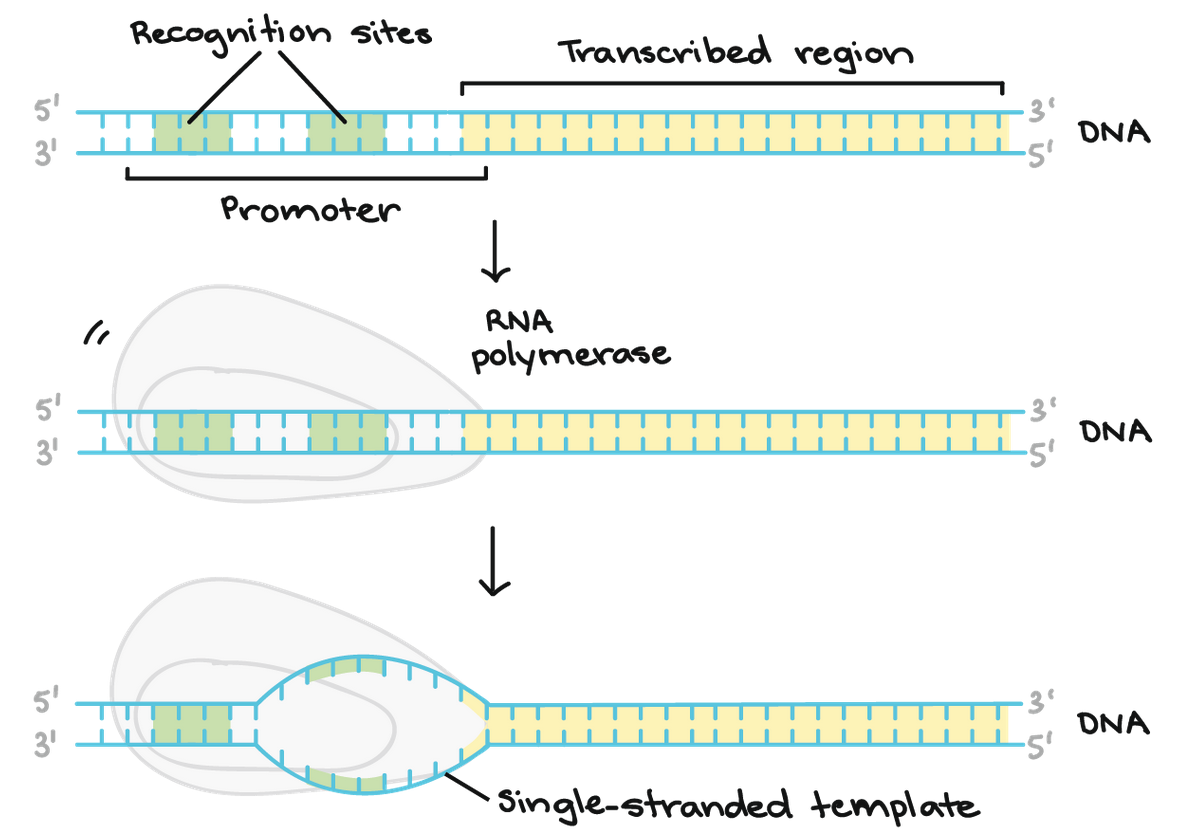

Stages of Transcription Transcription of a gene takes place in three stages, initiation, elongation, and termination. The following is an overview of what happens in bacteria.

- Initiation. RNA polymerase binds to a sequence of DNA called the promoter, found near the beginning of a gene. Each gene (or group of co-transcribed genes in bacteria) has its own promoter. Once bound, RNA polymerase separates the DNA strands, providing the single-stranded template needed for transcription.

- Elongation. One strand of DNA, the template strand, acts as a template for RNA polymerase. As it “reads” this template one base at a time, the RNA polymerase builds an RNA molecule out of complementary nucleotides, making a chain that grows from 5’ to 3’. The RNA transcript carries the same information as the non-template (coding) strand of DNA, but it contains the base uracil (U) instead of thymine (T).

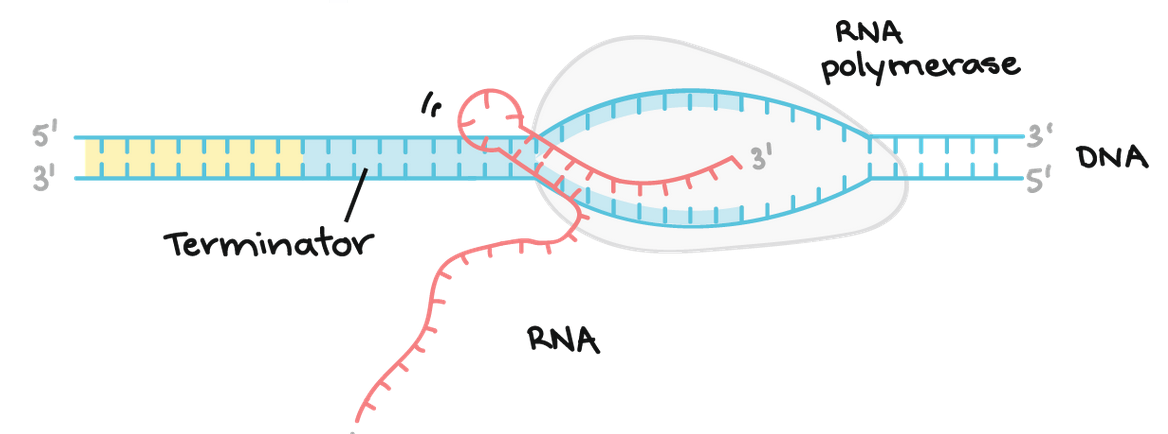

- Terminition. Sequences called terminators signal that the RNA transcript is complete. Once they are transcribed, they cause the transcript to be released from the RNA polymerase. An example of a termination mechanism involving the formation of a hairpin in the RNA is shown below.

Eukaryotic RNA Modifications In bacteria, RNA transcripts can act as messenger RNAs (mRNAs) right away. In eukaryotes, the transcript of a protein-coding gene is called a pre-mRNA and must go through extra processing before it can direct translation.

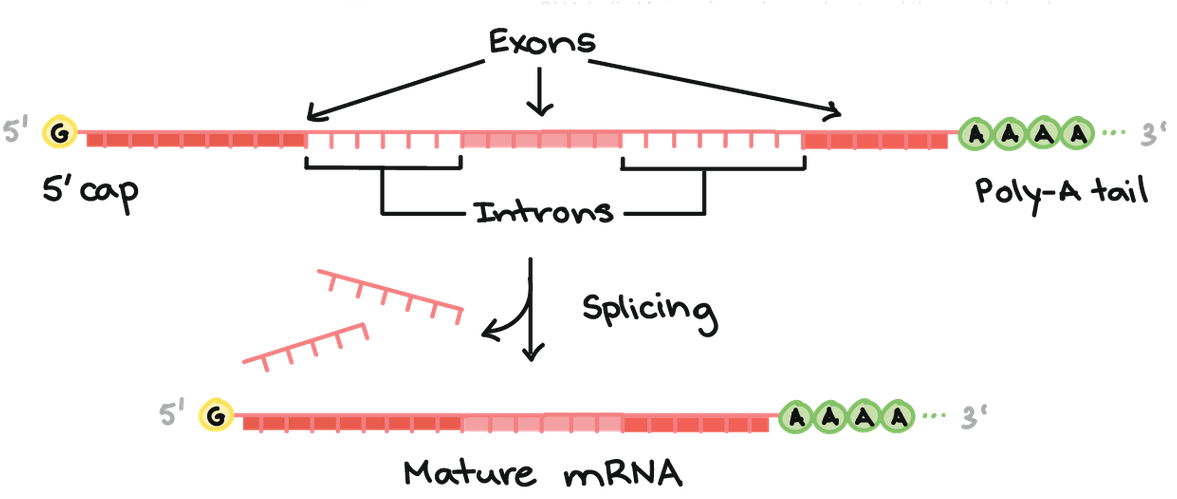

- Eukaryotic pre-mRNAs must have their ends modified, by addition of a 5’ cap (at the beginning) and 3’ poly-A tail (at the end).

- Many eukaryotic pre-mRNAs undergo splicing. In this process, parts of the pre-mRNA (called introns) are chopped out, and the remaining pieces (called exons) are stuck back together.

mRNA Processing Once RNA polymerase is done, the mRNA transcript has to be processed before it can make its journey out of the nucleus and to the ribosome. Processing has two phases: protection and splicing.

Protection During this phase, nucleotide sequences are each made of the mRNA transcript to protect it from degradation that can occur outside of the nucleus. The 5’ end of a single G nucleotide is attached to the 5’ end of the transcript. This is called the 5’ cap. At the 3’ end of the transcript, a long sequence of A nucleotides are attached. This is called the poly-A tail. The 5’ cap and the poly-A tail protect the mRNA transcript from attack by enzymes in the cytoplasm called exonucleases that specifically target mRNA molecules with exposed 5’ ends.

Splicing The purpose of splicing is to remove the introns from mRNA transcript. The purpose of splicing is to remove the introns from the mRNA transcript. Introns are sequences of RNA that don’t contain any information about how to construct a protein.

Introns are snipped out of an mRNA transcript by a complex of enzymes called a spliceosome. A spliceosome locates introns, cuts them out, and then fuses the remaining parts of the mRNA transcript back together. The parts of the mRNA transcript that aren’t spliced out by the spliceosome are called exons. In contrast to introns, exons are the part of an mRNA transcript that actually contain assembly instructions for a protein. Many call the mRNA transcript that still contains introns pre-mRNA, and the intron-free transcript that the spliceosome produces primary mRNA (also called “mature mRNA” by some authors).

End modifications increase the stability of the mRNA, while splicing gives the mRNA its correct sequence. (If the introns are not removed, they’ll be translated along the exons, producing a “gibberish” polypeptide).

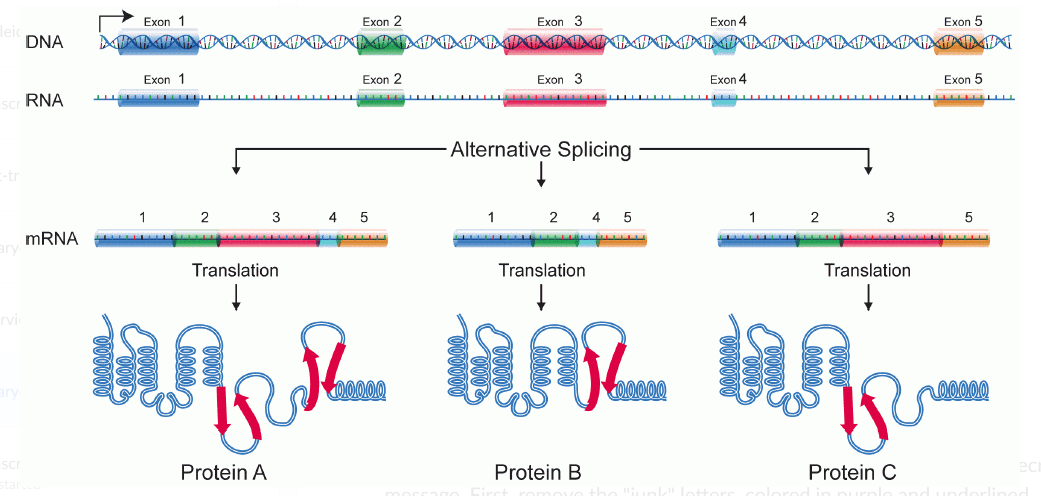

Alternative Splicing Splicing does allow for a process called alternative splicing, in which more than one mRNA can be made from the same gene. Through alternative splicing, we (and other eukaryotes) can sneakily encode more different proteins than we have genes in our DNA.

In alternative splicing, one pre-mRNA may be spliced in either of two (or sometimes many more than two!) different ways. For example, in the diagram below, the same pre-mRNA can be spliced in three different ways, depending on which exons are kept. This results in three different mature mRNAs, each of which translates into a protein with a different structure.

Transcription happens for individual genes Transcription is controlled individually for each gene (or, in bacteria, for small groups of genes that are transcribed together). Cells carefully regulate transcription, transcribing just the genes whose products are needed at a particular moment.